In his book Great instruction, great achievement for students with disabilities: A road map for special education administrators, O’Connor (2016) offers important insights about classroom instruction for special education students. Most students identified for special education services spend much of their school day in general education classrooms. They are expected to meet the same grade-level standards as all students; therefore, while universal, or whole class, instruction should be excellent for all students, this is especially true for students with disabilities. O’Connor also acknowledges that effective instruction for all, but especially for special education, should include attention to literacy development in all content areas. At the Collaborative for Teaching and Learning, we know the strategies and instructional practices that are really effective and needed by all students are especially effective for students in special education. Our Adolescent Literacy Model (ALM) provides a focus on school-wide content literacy coupled with high quality instructional practices and gives teachers tools and strategies for designing and implementing lessons that can specifically meet the needs of students in special education programs.

O’Connor outlines the characteristics he deems essential to great instruction as:

- Guided by the performance standards

- Rigorous with research-based practices

- Engaging and exciting

- Assessed continually to guide further instruction

- Tailored in flexible groups

Teachers implementing ALM use literacy strategies grounded in research to engage every student in the room in reading, writing, speaking, and listening in order to learn grade-level content. ALM strategies provide whole group, small group, and individual opportunities for students to think, share ideas, and get feedback from the teacher and peers. When done regularly, students with disabilities get the practice and support they need to achieve at higher levels.

While excellent whole group instruction is critical to achievement, students with disabilities do require specially designed instruction based on their needs, as documented in their Individual Education Plans (IEPs). There is an expectation of some kind of differentiation, and while each student’s disability may require different adaptations, there are some practices that, when combined with effective universal instruction, allow teachers to meet students’ special needs and increase achievement (O’Connor, 2016). Many of these practices are inherent in the implementation of ALM.

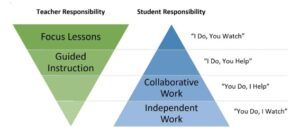

One of these is explicit instruction. When teachers follow the sequence of “I do-We do-You do”, students get clear modeling and guided practice before transitioning to independent practice. Explicit instruction provides organization and clarity for students as they process new information since students with disabilities may struggle with ambiguity or lack of structure, at least when learning something new. In our foundational training for ALM, we spend time with teachers discussing the importance of gradual release, especially when students are learning a new process. Similar to “I do-We do-You do”, gradual release dictates that students are active in the process, even when the teacher is the one “doing” the new process. Students first watch and then provide commentary to “help” the teacher do the process correctly. Then they are ready to try on their own but in a structured way with feedback. When teachers organize lessons in this way, all students benefit, and especially students with disabilities.

Another important element of specially designed instruction is multiple practice turns with feedback. Students with disabilities need more opportunities to practice skills and content, yet they often get less. Perhaps the students engage in avoidance behaviors or are skilled at appearing to be engaged so as to not draw attention to themselves. Perhaps the teacher does not include multiple practice opportunities in the lesson because of time and pacing constraints. However, we know from our experiences learning anything new, without sufficient practice it is difficult to achieve mastery. In addition to multiple practice turns, students need immediate feedback while practicing so that accurate, appropriate actions and ideas are reinforced. Without feedback, misconceptions go unchecked, and bad habits are perpetuated. This is one reason we champion the importance of structured student-to-student dialogue and small group activities. Teachers may not get to every student every day to provide feedback, and students benefit from getting feedback from each other. Students can also be given self-evaluation prompts to help them determine if they are on the right track or need to self-correct. Peer and self-feedback should not be the only sources of feedback, but balanced with frequent teacher feedback, students in special education will get the specific guidance needed to learn more deeply.

A third important component of specially designed instruction, according to O’Connor (2016) is explicit, embedded vocabulary instruction. Many of the traditional methods for teaching vocabulary do not prove to be effective for most students but especially not for students in special education. Research shows that students need a minimum of 17 exposures to master new words but only if those exposures happen in a specific context (Kamil, et al., 2008). When new vocabulary is presented without a contextual connection, students need at least 70 exposures (Chonko, 2019). Vocabulary development is critical to building background knowledge and creating schema, things often underdeveloped for students with disabilities. Therefore, the time spent allowing students to experience and practice with vocabulary in a context through reading, writing, speaking, and listening will pay multiple dividends for all students but especially for those with special needs. When students learn vocabulary they are learning content! The Vocabulary Development strategies of ALM provide teachers ways to intentionally include explicit vocabulary instruction in their daily lesson and unit planning. We have a moral imperative to ensure great instruction is happening in all of our classrooms, especially when it comes to students with disabilities. All students deserve intentional, effective, engaging learning experiences, but students with special needs require it. By implementing the strategies of ALM, teachers can better prepare to meet the needs of all of their students, but most importantly, those of their special learners.

We have a moral imperative to ensure great instruction is happening in all of our classrooms, especially when it comes to students with disabilities. All students deserve intentional, effective, engaging learning experiences, but students with special needs require it. By implementing the strategies of ALM, teachers can better prepare to meet the needs of all of their students, but most importantly, those of their special learners.

Chonko, B. (2019, June 7). Why you should abandon word lists. Comprehensible RVA. https://comprehensiblerva.wordpress.com/2019/06/07/why-you-should-abandon-vocab-lists/

Kamil, M. L., Borman, G. D., Dole, J., Kral, C. C., Salinger, T., & Torgesen, J. (2008). Improving adolescent literacy: Effective classroom and intervention practices: A Practice Guide (NCEE #2008-4027). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/PracticeGuide/8

O’Connor, J. L. (2016). Great instruction, great achievement for students with disabilities: A road map for special education administrators. Council of Administrators of Special Education.