In the United States, K-12 schools are legally required to ensure that Multilingual Learners (MLs) can participate fully in all educational programs, as outlined in both the Civil Rights Act and the Every Student Succeeds Act. Since it is estimated that by 2025, MLs will be 25% of the student population in the U.S., practically every teacher will have the opportunity to serve these students in their classrooms with the responsibility of ensuring that ML students have the support needed to access grade level core curriculum. CTL’s Adolescent Literacy Model (ALM) helps teachers address five critical literacy subdomains that students must develop in order to learn content in any academic discipline: Vocabulary Development, Academic Dialogue, Reading Comprehension, Writing to Learn, and Writing to Demonstrate Learning. When MLs, alongside their native English-speaking classmates, can engage in intentionally selected strategies within these subdomains, they will improve their English proficiency as they learn important content.

Vocabulary is an important foundation for understanding content. At the beginning of a unit, teachers should identify a set of vocabulary words that are key to understanding the content of that unit and plan for how students will authentically engage with the words throughout the unit. All students – and MLs particularly – need repeated exposure and practice with academic vocabulary in different contexts. Research tells us that students need at least 17 contextual exposures to master understanding of new vocabulary words (Kamil, et al., 2008). This will not happen merely with drill, repetition, or copying definitions. Strategies such as the Frayer model and Interactive Word Wall can give students contextualized practice with new academic vocabulary. All students need repeated contextualized practice with new academic vocabulary, but teachers may need to build in additional scaffolds for MLs, such as word banks, nonlinguistic representations, and student-friendly definitions of words, and then gradually pull back such supports as the students increase their English vocabulary (Fenner & Snyder, 2017).

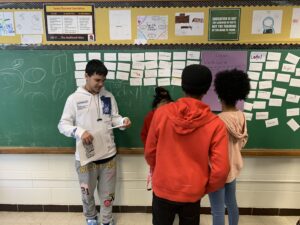

In order to process, refine their thinking, and learn from others, all students need frequent opportunities to talk about content. In ALM, we strongly advocate for structured Academic Dialogue activities focused on content. The key word is “structured” – these experiences must be planned so that every student is expected to pre-plan their discussion points, cite textual evidence, and listen with intent to the ideas of their peers. This fosters active learning of content while building community and communication skills. Not surprisingly, MLs benefit exponentially from structured Academic Dialogue in their classes. The benefits of regular practice with academic discourse for MLs include strengthening vocabulary, developing oral language, building a foundation for reading and writing, and deepening critical thinking skills (Fenner & Snyder, 2017). The Academic Dialogue strategies of ALM, such as Think-Ink-Pair-Share, Give One, Get One, and Paired Verbal Fluency, allow teachers to thoughtfully plan for students to interact with peers, build vocabulary, and deepen content understanding in a purposeful, supportive way.

A common challenge for teachers across disciplines is supporting non-proficient readers as they struggle with grade-level texts. Often, MLs are not yet proficient readers, and there is a temptation to only give them lower Lexile texts to reduce frustration and increase comprehension. Unfortunately, this has proven to be a disservice. Struggling readers, including MLs, will not improve their ability to read grade-level texts if they do not get access to and practice with grade-level texts; however, they need scaffolding and strategies to help them. Fenner & Snyder (2017) recommend some specific ways in which teachers can support MLs in reading complex, grade-level texts that include explicitly teaching needed background knowledge, academic vocabulary instruction, guiding questions to frame the reading, and text-dependent questions with sentence starters. Several of the reading comprehension strategies in ALM can support MLs – and their teachers – in this process. Anticipation Guides and KWL Charts allow teachers to assess the background knowledge of students so that critical gaps can be filled before reading. The Guide-O-Rama helps students familiarize themselves with the structure and key topics and could introduce big, guiding questions for students to consider as they get started with a text. Double Entry Organizers can be differentiated to provide extra structure or scaffolding for MLs during the reading process to capture important ideas and student thinking and can be used for different purposes during multiple reads of a text.

As the number of Multilingual Learners in our K-12 schools continues to climb, all teachers must be prepared to meet their needs as part of regular, core instruction. Federal law dictates that MLs have equitable access to grade level standards, and this cannot be the sole responsibility of ESL teachers. General education teachers need training, resources, and support to serve their MLs. Fortunately, the Adolescent Literacy Model embraces the idea that literacy is how we learn and provides a school-wide model for embedding research-based strategies in all disciplines so that students have frequent opportunities to read, speak, write, and listen about content grounded in vocabulary. While MLs have the added need to develop English language proficiency as they learn content, the considerations and strategies for supporting MLs with literacy are, in fact, highly effective for all students.

References

Collaborative for Teaching and Learning. (2022). Foundations of content literacy: An instructional framework for comprehensive literacy instruction in all content areas. Collaborative for Teaching and Learning, Inc.

Fenner, D. S., & Snyder, S. (2017). Unlocking English learners’ potential: Strategies for making content accessible. Corwin.

Kamil, M. L., Borman, G. D., Dole, J., Kral, C. C., Salinger, T., & Torgesen, J. (2008). Improving adolescent literacy: Effective classroom and intervention practices: A practice guide (NCEE#2008-4027). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/PracticeGuide/8