It’s late August and students, parents and teachers are sliding into back to school routines. Lunchboxes have been chosen. Backpacks have been selected. Notebooks have been purchased. Teachers have prepped their classrooms. Rosters are printed and teachers have planned lessons. When students and teachers arrive at this place together, the classroom, there is one element of classroom dynamics that can not be fully anticipated and that is “Which of the students beat summer slide?” This is a question that classroom teachers across the country, particularly in rural America, will need to ask in order to fully prepare for the classes of 2013-2014.

It’s late August and students, parents and teachers are sliding into back to school routines. Lunchboxes have been chosen. Backpacks have been selected. Notebooks have been purchased. Teachers have prepped their classrooms. Rosters are printed and teachers have planned lessons. When students and teachers arrive at this place together, the classroom, there is one element of classroom dynamics that can not be fully anticipated and that is “Which of the students beat summer slide?” This is a question that classroom teachers across the country, particularly in rural America, will need to ask in order to fully prepare for the classes of 2013-2014.

In a January 2012 report by the Rural School and Community Trust Policy Program Why Rural Matters, it is estimated that approximately 25% of America’s schoolchildren attend a rural school and 38.5% of Kentucky schoolchildren are rural students, with 49.8% of Kentucky schools being rural. The Rural School and Community Trust estimates that between 1999 and 2009 the enrollment in rural districts increased by 1.7 million students, a growth rate of 22%, as compared to a non-rural enrollment growth rate of only 1.7%. This outpacing suggests that rural education deserves increased attention (Why Rural Matters, 2011-2012).

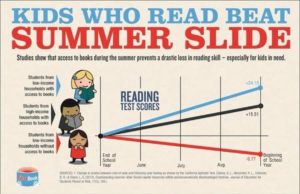

Why does rural matter? Two out of 5 students attending schools in a rural district live in poverty (as defined by being recipients of the federally-funded free or reduced priced meal program). This rate has increased by nearly a third in 9 years, particularly in the South, Southwest, and parts of the Appalachia (Why Rural Matters, 2011-2012).Rural matters because summer reading slide can be attributed to family income and geographical isolation when students in rural, poverty areas do not have access to print-rich environments or literary-rich experiences during the summer months. During the school year, parents of children in low-income households rely primarily on educational institutions to provide learning opportunities to their children (USED, 1993).

Although public libraries are often established in these communities, transportation to and from and proximity to residences remain impediments for these children. If a community library does exist for a child in a low-income household, if he has to travel more than six blocks from his home to get to a library, library use drops off (Frazen & Allington, 2003). In middle to upper-income households, parents are more likely to take children on excursions and to libraries, travel, and read with them daily (Entwisle et al., 1997).

The faucet theory, developed by Entwisle (1997) points toward the belief that during the academic school year, the faucet to resources is turned on for all students and during the summer break, the faucet to resources is turned off for students of poverty. This theory indicates that U.S. students of poverty regress over the summer break in the skills and knowledge gained during the school year. The authors explain it as:

When school was in session, the resource faucet was turned on for all children, and all gained equally; when school was not in session, the school resource faucet was turned off. In summers, poor families could not make up for the resources the school had been providing, and so their children’s achievement reached a plateau or even fell back. Middle-class families could make up for the school’s resources to a considerable extent. … Home resources matter mainly—or only—in summer (Entwisle, Alexander, & Olson, 2001, p. 12).

During the school year, teachers and librarians schedule library time, arrange field trips and plan reading activities. Opportunities are provided to enhance and strengthen student reading skills throughout the school year. In addition, back to school is a critical time for teachers as they think about where their students start the year, where they should be when they leave, and what skills and resources they might need the following summer. Here are 11 ways schools can begin planning for summer reading:

1. Allow students to check out school library books for the summer.

2. Give away books.

3. Create a “Books for a Buck” program.

4. Create an “honor library” that provides a steady supply of new and used paperbacks.

5. Create a summer school voluntary reading program.

6. Check with local stores like “Half Price Books” and ask if they’ll donate books for summer reading.

7. Encourage students to track their summer reading.

8. Create an online book club.

9. Develop “Books Not to Miss” lists and/or bookmarks for students.

10. Inform parents of local opportunities.

11. Develop a “Summer Reading” page on your school/district website.

What intentionality is being taken to proactively address summer reading slide in your community? It’s not too early to start the conversation and begin planning.

References

Entwisle, D., Alexander, K. & Olson, L.S., (1997). Children, Schools & Inequality. Boulder,

Colorado: Westview Press.

Entwisle, D.R., Alexander, K.L., & Olson, L.S. (2001). Keep the faucet flowing: Summer

learning and home environment. American Educator, 25(3),10–15, 47.

Rural School and Community Trust. (2012). Why rural matters 2011-12: Statistical indicators of the condition of rural education in the 50 states. Retrieved from http://www.ruraledu.org/articles.php?id=2820.