Have you met Jerome? You should.

Have you met Jerome? You should.

When we unpack the new Artful Reading module, The Right Word, and teachers read Peter H. Reynolds’ picture book, The Word Collector for the first time, they all, without fail, meet Jerome and fall in love.

Why do they fall in love?

Because Jerome has a heart for words…he is an experimenter with words…he is a Word Collector.

We all know the crucial role words, or vocabulary, play in students’ ability to read, comprehend, make sense of the world, and express that understanding. We regularly identify Tier 2 and Tier 3 vocabulary words for direct instruction, we search endlessly for ways to put that instruction in a meaningful context, and we design instructional routines we believe students will find engaging. We struggle, however, to build in our students the things that make Jerome so special. It isn’t the size of his vocabulary; it isn’t his ability to decode words, nor is it his ability to use these words accurately when he writes or speaks.

It IS Jerome’s attitude towards, approach to, and belief about words that make him so special.

Jerome is mindful of and curious about words.

Jerome is flexible in his approach to making sense of words.

Jerome is unafraid of new vocabulary.

While Jerome’s independent ability and motivation to learn words on his own (incidental or independent acquisition) may seem far from our student’s current abilities and motivation, let us set aside the idea that incidental learning of vocabulary is random and outside of our control. This new school year, what if we embrace the idea that incidental learning can be influenced by the teacher when we endeavor to model, teach, and create a group of students who are mindful, flexible, and unafraid of new words?

Below are a few ways we at CTL encourage the teachers we collaborate with to foster “Jerome-like” students.

Vocabulary Mindfulness

Jerome consumes words from a variety of places, and he is regularly mindful of new words he comes across. How can we build this in our students? As with anything, we model this attitude ourselves. And the perfect place to model this attitude? When reading aloud to our students. The classroom Read-Aloud isn’t a strategy that should be reserved for early elementary but should be used through all grade levels. Author Jim Trelease published in The Read-Aloud Handbook that a student’s reading level does not catch up to his listening level until the eighth grade (2013). If you spend any time in high schools, you will hear this same conclusion reiterated. When coupled with the need to provide exposure to a rich variety of vocabulary, we can see a call to continue reading aloud to students well past 8th grade. It is in these Read-Alouds that teachers have the opportunity to model Jerome-like behaviors.

- Pausing to unpack an author’s word choice.

- Backing up to reread a word you are unsure of and model independent sense-making strategies (i.e., synonym swaps, context clues).

- Crafting a mental semantic or thematic map of words.

- Elaborating on a newly discovered connotation of a known word in a particular context.

Modeling this attitude and behavior while reading aloud tells children that this word “mindfulness” or “consciousness” is healthy, useful, and carried into adulthood. We are not memorizing a list of words for an exam or upcoming project, but instead becoming “naturally” mindful and curious about words we encounter.

Flexible Approach to Vocabulary

Our model Jerome begins by making lists, then categorizing those lists, and ultimately making new and interesting word pairings. His approach to words changes as necessary and helps him make sense of the words in ways he.is.ready.for.

Our model Jerome begins by making lists, then categorizing those lists, and ultimately making new and interesting word pairings. His approach to words changes as necessary and helps him make sense of the words in ways he.is.ready.for.

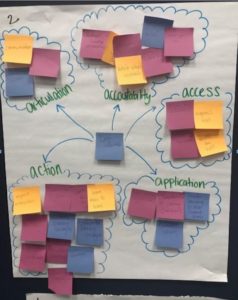

In our work in Middle and High School with CTL’s Adolescent Literacy Model, we encourage students to use their critical thinking skills as they play with and rethink their understanding of words us a strategy called “List.Group.Label.” Students self-identify words significant to a body of work, determine categories that make sense to them given the context and then sort the words into those categories. Done in small groups or independently, students then share their thinking with others, can sort anew and relabel as understanding grows, and are given space to justify their evaluation. As teachers, we are open to all student responses, probe to help US “see” student thinking, and in this way, can formatively assess student understanding of both concepts and terms.

No.Fear. Vocabulary Mindset

Never do we see Jerome pause to ask an adult or “word authority” what a word might mean, never do we see him shy away from a paring he might be unsure of (i.e., “savor dreams,” or “cascading stars”), and never do we see him choosing a “safe,” known word when he could stretch and try a new one.

As teachers, the best way we can create this No.Fear. Mindset in the classroom is by praising students for their risk-taking with word choice and take a page out of Peter H. Johnston’s book, Choice Words (2004). In a book focused on the importance of the language teachers use and how that language shapes our students, Chapter Two has special significance for creating a No.Fear. vocabulary environment. Whatever teachers “Notice & Name” will shape what students see, notice, believe and do. If we notice and praise students for stretching to use a new word, if we name aloud a student uncovering a sophisticated connotation of a known word, if we notice and support a student who has used a word incorrectly but was brave enough to take the risk, if we make known our own missteps or new learning with vocabulary, students will also notice, name, note, praise, and seek out these same behaviors. In short, if we have and support a No.Fear. belief system around vocabulary, our students will too.

As Johnston reports from Harre & Gillet’s The Discursive Mind, “once we start noticing certain things, it is difficult not to notice them again; the knowledge actually influences our perceptual systems.” It is within our influence as educators to shape student perception of, or mindset towards, new vocabulary.

While the strategies listed above cannot be assessed on a quiz every Friday, they will pay dividends in the long-term literate life of your students. If you are looking to create a Jerome-like environment with your students this year, we suggest you check out Bringing Words to Life (2013) to read about some tried and true strategies for both intentional and incidental vocabulary acquisition.

So have you met Jerome? He’s knocking on your classroom door and needs you to show him the way.