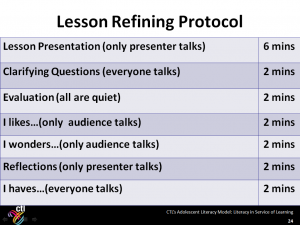

In a recent English Language Arts academy facilitated by CTL, teachers used a critical friends protocol similar to the one show below to provide feedback to each other after three days of creating inquiry-based units. Among the interesting comments shared was this one:

“I like that you are not teaching a novel, per se, but are using a novel to get students thinking about concepts and issues.”

A longstanding mindset of English Language Arts teachers is to describe their current unit or chunk of curriculum as “Teaching (fill in any title)”, as in, “I am teaching To Kill a Mockingbird this month.” In many instances, this planning framework results in students completing activities related to a novel, play, or nonfiction piece that are not very congruent with the skills and knowledge required in standards. More importantly, reading-related activities can be limited in purpose; that is, they may end with comprehension and personal connection and fail to require students to develop deeper connections between a variety of texts and the exploration of ideas.

The Common Core State Standards clearly indicate a shift away from the teaching-to-a-title mindset and toward an approach of inquiry, engaging students in investigations, analysis, and other types of critical thinking. This shift is not to ignore what happens in a book or the literary approaches authors use to build narrative, but to build student expertise in understanding the craft of writing while placing greater emphasis than before on synthesis of concepts, ideas, and important questions. This shift makes clear that reading and writing are flipped sides of the same process, and by having students interact with text for a purpose, they will have a better chance of becoming independent and proficient readers. That purpose, to demonstrate, through a product, that students can use the knowledge they have gained, is central to the world of adult work and college studies.

For many ELA teachers who entered the profession with strong literary backgrounds rooted in a love of fiction, these changes are out of a comfort zone, and there can be confusion about what an ELA classroom should look like. A review of Appendix B of the Common Core State Standards for ELA will indicate that ELA content is a conduit in a broader spectrum of student meaning making, with a more refined vision of narrative’s role in the process than has perhaps existed in the past.

Teachers, who are accustomed to an ever-revolving door of reform initiatives, changes, and fads in the classroom are adjusting to the Common Core shifts, which offer a very focused vision of appropriate student learning in preparation for college and beyond. The standards offer an “addition to” the literary analysis ELA teachers love so much, while also resulting in the revision or replacement of many of the activities-based lessons in “novel units”, which served in the past to engage students, but not necessarily to support close reading, analysis, and synthesis of information. Until now, for example, pairing literary and nonfiction works has not been a widespread or comprehensive practice since “teaching the novel” was the aim of a unit.

Teachers, who are accustomed to an ever-revolving door of reform initiatives, changes, and fads in the classroom are adjusting to the Common Core shifts, which offer a very focused vision of appropriate student learning in preparation for college and beyond. The standards offer an “addition to” the literary analysis ELA teachers love so much, while also resulting in the revision or replacement of many of the activities-based lessons in “novel units”, which served in the past to engage students, but not necessarily to support close reading, analysis, and synthesis of information. Until now, for example, pairing literary and nonfiction works has not been a widespread or comprehensive practice since “teaching the novel” was the aim of a unit.

Educator Renee Boss expounds on this shift in her blog, Narrative and Informational Texts and the Common Core which cuts through the either-or mentality of literary vs. informational reading and offers a more complete view of learning.

For all of the talk in recent years about increasing rigor in instruction and a growing bank of useful information available to assist with that change, few initiatives have yet to impact overall teaching practice in a sustaining manner. However, there seems to be collective and growing vision among educators about what school should look like in this century. For ELA teachers using an inquiry-based approach to teaching literacy skills, the following student characteristics from the NASSP article, “Recognizing Rigorous and Engaging Teaching and Learning”, should look familiar:

- They exhibit a set of behaviors that include task persistence, regular attendance, and sustained attention.

- Emotionally, they demonstrate excitement, interest in learning, and a sense of belonging.

- They show cognitive engagement by taking on academic challenge, positive self concepts, and a desire to continue learning.

Now, more than ever, we are expecting students to engage in work with an authentic purpose. And we are expecting teachers to supply the structure and feedback that will nurture students toward independent thinking and proficient expression of that thinking. This shift doesn’t mean we should throw out the novels; rather, it means we should rethink our purpose in having students read novels and literary nonfiction, and include students in finding that purpose.