Link to downloadable PDF version

Authored by Dr. Deborah Walker and Barb Myerson-Katz

Introduction

“Within the United States and across nations, there seems to be consensus that teacher quality is the most important school-based variable in determining how well a child learns. While such an observation hardly sounds like headline news, it is a milestone in the development of teaching as a profession. It suggests where investments should be made if people really are serious about student learning. It also explains why policymakers and the public should care about what it means to be an effective teacher and what it will take to create and sustain a teaching workforce defined by accomplished practice. Teachers, administrators, and others whose work is designed to support best practice in our schools must seize this moment to rethink every aspect of the trajectory people follow to become accomplished teachers. Getting that path right and making sure all teachers follow it asserts the body of knowledge and skills teachers need and leads to a level of consistent quality that is the hallmark of all true professions. No profession has ever been established in any other way, and there is no reason to believe that teaching is or should be different.”

~ Ronald Thorpe, Late President and CEO, National Board for Professional Teaching Standards in “Sustaining the Teaching Profession”

The late Ronald Thorpe, former President and CEO of the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, introduced his 2014 New England Journal of Public Policy article on “Sustaining the Teaching Profession” with the notion that the culture of the teaching profession must expand and change in order to achieve the essential goal of advancing learning for all students. Central to that idea is the belief that expansion and change is also critical to advance the development of all teachers – to lift the culture of teaching, and thereby, the profession itself.

In the current high stakes testing and accountability environment that prevails in many schools nationwide, there is arguably a crisis in the teaching profession marked by low morale among even some accomplished teachers, and low retention rates among many new teachers. From Quicksand to Solid Ground, a 2015 report on the infrastructure required to support quality teaching by Jal Mehta and others at the Transforming Teaching Project at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education, notes, “Teachers tell us that there is something awry…Many teachers bemoan the flat structure of the profession and the lack of opportunities to help their colleagues without losing touch with the classroom.” The report cites statistics indicating that many teachers believe professional learning is largely ineffective, and that many leave the classroom within their first five years, draining talent from the profession.

The longstanding mission of CTL, the Louisville, Kentucky-based nonprofit, matches a renewed emphasis in education on lifting the teaching profession through transformation of the roles and responsibilities of teachers themselves. For more than 20 years, CTL has worked to advance excellence in teaching and school leadership through high quality, job embedded professional development for teachers and administrators, shaped by and responsive to the actual needs of students and schools. CTL was a primary collaborator with the Kentucky Department of Education and others on the recent development of the Kentucky Teacher Leadership Framework.

The longstanding mission of CTL, the Louisville, Kentucky-based nonprofit, matches a renewed emphasis in education on lifting the teaching profession through transformation of the roles and responsibilities of teachers themselves. For more than 20 years, CTL has worked to advance excellence in teaching and school leadership through high quality, job embedded professional development for teachers and administrators, shaped by and responsive to the actual needs of students and schools. CTL was a primary collaborator with the Kentucky Department of Education and others on the recent development of the Kentucky Teacher Leadership Framework.

This policy paper was conceived as a call to action to elevate the teaching profession, through sometimes small but intentional shifts in the way teachers work, that can nevertheless have significant positive impact on both the teaching culture and student learning. The examples noted here suggest potentially scalable approaches to the challenge of improving both the teaching profession and student learning as a direct result. As Thorpe noted, the education community has long understood the elements required to improve teaching. The challenge is to translate that knowledge into practice. The cases that follow demonstrate that first steps toward improved culture and practice are not only desirable but achievable.

Adapted from the Center for American Progress 2015 report, Smart, Skilled and Striving: Transforming and Elevating the Teaching Profession, significant improvement in teaching overall requires –

- More selective criteria for entry into teacher preparation programs

- More rigorous teacher preparation program coursework

- Higher quality teacher preparation field training experiences

- Improved licensure examinations to raise the bar for entry into the teaching profession

- Increased teacher compensation, and differentiation of compensation based on individual teacher responsibilities and performance

- Ongoing professional learning from beginning of every teacher’s career

- Professional learning aligned with student and teacher needs

- Redesigned school schedules to accommodate shifts in teacher practice

- More opportunities for teachers to take leadership roles, including while continuing to teach

- Higher standards for attaining tenure

- Improved training for school leaders to support teachers

The focus of this paper is on two broad categories largely under the control of individual districts and schools – opportunities for ongoing professional learning, feedback and collaboration, and opportunities for differentiated teacher roles and leadership that facilitate career advancement and address teacher and student needs. Both have the potential for significant positive impact on the culture of teaching, and in some cases require relatively minor adjustments in expectations and practices.

for differentiated teacher roles and leadership that facilitate career advancement and address teacher and student needs. Both have the potential for significant positive impact on the culture of teaching, and in some cases require relatively minor adjustments in expectations and practices.

The ultimate challenge is to take knowledge about all the elements that can positively transform teaching and learning and implement them in replicable and sustainable ways. The exemplars that follow indicate that this is possible – both through larger, comprehensive models, and through relatively simple, smaller-scale shifts in attitudes and practices by administrators and teachers that don’t require new or significant infusions of funding.

Research on Positive Teacher Culture

“The need to turn teaching into a respected profession has been part of the education discourse for at least a hundred years. It is widely recognized that we need to build the structures and processes to support adult learning, just as we do for children’s learning. But the field has been slow to act, and longstanding structures and institutions have proven difficult to change.”

~ Jal Mehta, et al., Transforming Teaching Project, Harvard University Graduate School of Education, From Quicksand to Solid Ground

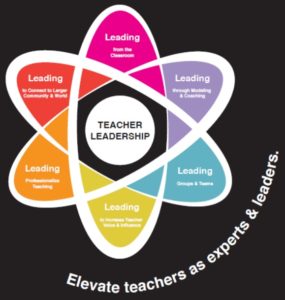

The recently adopted Kentucky Teacher Leadership Framework (https://ctlonline.org/kentucky-teacher-leadership-framework/), the graphic for which illustrates a re-conceptualization of the roles teachers can play in professionalizing teaching, is itself built around the concept of teachers as collaborative professionals. In the Framework’s introduction, Dr. Brett Criswell of the University of Kentucky notes, “Teacher leaders need to work together and work with others to be able to highlight features of effective pedagogical practice.” As teachers increase their leadership capacity, he says, “their sphere of influence grows,” eventually encompassing other colleagues and the entire school system. The Framework outlines six spheres of teacher leadership –

- Leading from the Classroom – Developing capacities of students and self

- Leading through Modeling and Coaching – Developing capacities of peers

- Leading Groups and Teams – Contributing to positive school change to enhance student learning

- Leading to Increase Teacher Voice and Influence – Working to enlarge teachers’ role in decision making beyond the classroom

- Leading to Professionalize Teaching – Reforming educational system to increase opportunities for teachers to learn and lead

- Leading to Connect to the Larger Community or World – Expanding the world of the classroom beyond the school

The Kentucky Teacher Leadership Framework aims to standardize professional practices and goals for all Kentucky teachers. In the same spirit, Ronald Thorpe noted that in high caliber professions like medicine, “the content of preparation programs is standardized around principles of accomplished practice.” He, too, believed that extensive professional learning and mentoring by more experienced colleagues was central to such accomplishment, and advocated for residency experiences for teachers, analogous to those required for doctors. These, he said, “would have a major impact on the culture of the (teaching) profession and the quality of teaching and learning in schools.”

Recent literature on teaching likewise supports a similar focus on teacher agency in decision making on curricula and strategies, teacher-directed professional learning, and, related to both of these, extensive opportunities for teacher collaboration:

- Among the compelling findings of the Center on Education Policy’s May 2016 report, Listen to Us: Teacher Views and Voices, was that vast majorities of more than 3,000 teachers surveyed nationwide, “believe their voices are not often factored into the decision-making process at the district, state or national levels” – and, in contrast, that collaboration with colleagues is valuable.

- In a 2016 Ford Foundation-commissioned report, Barnett Berry, Founder and CEO of the Center for Teaching Quality, noted that hybrid roles that enable teachers to make decisions about programs, materials and resources ensure not only a collaborative vision and strategy to reach all students, but increased investment and excitement on the part of the teachers themselves. Berry’s research suggests that such “teacher-powered” schools decrease discipline issues and safety concerns, and increase graduation rates and college attendance for students.

Linda Darling-Hammond and others at the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education notes in a 2010 research brief that high performing school systems around the world emphasize universal mentoring for all beginners, as well as extensive opportunities for ongoing professional learning, and teacher involvement in decision making. “In high achieving nations,” they wrote, “teachers’ professional learning is a high priority, and teachers are treated as professionals.”

Linda Darling-Hammond and others at the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education notes in a 2010 research brief that high performing school systems around the world emphasize universal mentoring for all beginners, as well as extensive opportunities for ongoing professional learning, and teacher involvement in decision making. “In high achieving nations,” they wrote, “teachers’ professional learning is a high priority, and teachers are treated as professionals.”

- A recent study of teacher professional development in Shanghai, Singapore, and British Columbia by the National Center on Education and the Economy (NCEE) notes that in all three places, teachers are expected to collaborate to improve effectiveness and therefore student learning. The process advances their teaching careers – in the same way, for example, that new attorneys learn from seasoned colleagues as they advance their careers within a law firm. In contrast, advancement for a teacher within a school traditionally has been limited to the role of principal, who often does not have teaching responsibilities. As NCEE director Marc Tucker notes regarding advancement in teaching in the United States, “There’s no reward for getting better at it. There’s no career in teaching. There’s no high amounts of responsibility to aspire to [sic].”

- The Center for American Progress 2015 report cited above suggests that to attract and retain excellent teachers, the profession should provide, “a more gradual on-ramp to a full-time teaching experience,” that includes, “intensive coaching and mentoring, co-teaching models and experiences, teacher residency programs, and/or a reduced course load for beginning teachers,” along with increased opportunities for teachers to take leadership roles – including mentoring new or struggling teachers, planning and facilitating professional development, and providing feedback to colleagues. A caveat here in the history of such an initiative more than two decades ago: The California New Teacher Project, which funded reduced class loads and extensive mentoring for rookie teachers, resulted in improved performance of both students and teachers, but that success did not continue when the efforts did not take hold in a systemic way. Such failures to sustain and scale educational advances cause the same problems to resurface – with the need to be addressed – again and again.

- The National Education Association’s Commission on Effective Teachers and Teaching (CETT), made up of accomplished teachers and education leaders from across the United States, likewise stated in 2010 that teacher collaboration supports student learning, and called for increased collaborative engagement for teachers, which they termed, “crucial to effective teaching.” CETT noted the related need to connect professional responsibility and student learning.

- An Alliance for Excellent Education 2008 issue brief likewise stated that “comprehensive induction,” including mentoring, collaboration and ongoing professional learning and feedback among new and experienced teachers, increases the likelihood that quality teachers will continue teaching.

Seeking Examples of Positive Teaching Culture

In addition to the research cited above that provides a clear rationale for what Barnett Berry terms “teacher-powered” schools, CTL sought local examples of teacher-directed leadership, professional learning and collaboration that are having a positive effect not only on teachers themselves, but on student achievement and school culture.

For the purposes of this paper, we interviewed four teachers, two principals, one district administrator, one state department of education effectiveness coach, one member of a university education faculty who is also a recent district administrator, and one education consultant who has developed a comprehensive model for differentiating teacher roles. The Kentucky educators overall represent multiple regions of the state. We sought input from teachers who are currently or have recently been involved in either formal or informal teacher leadership programs at state, district or school levels – and coincidentally, three of the four work in Jefferson County (Kentucky) Public Schools, the largest district in Kentucky with more than 150 schools and representing both urban and suburban settings. However, the blog post about virtual collaboration that prompted one of the teacher interviews was written while that teacher was working in a different Kentucky district.

For the purposes of this paper, we interviewed four teachers, two principals, one district administrator, one state department of education effectiveness coach, one member of a university education faculty who is also a recent district administrator, and one education consultant who has developed a comprehensive model for differentiating teacher roles. The Kentucky educators overall represent multiple regions of the state. We sought input from teachers who are currently or have recently been involved in either formal or informal teacher leadership programs at state, district or school levels – and coincidentally, three of the four work in Jefferson County (Kentucky) Public Schools, the largest district in Kentucky with more than 150 schools and representing both urban and suburban settings. However, the blog post about virtual collaboration that prompted one of the teacher interviews was written while that teacher was working in a different Kentucky district.

Taken together, they suggest that certain common steps to increase opportunities for teacher leadership, teacher-directed professional learning and collaboration can positively influence teacher culture, and therefore student learning. The simultaneously good and challenging news is that these shifts seem to require more a change of will than an increase in dollars, and can be accomplished both within the context of a broad, systemic model, or relatively simply, under the auspices of an enlightened administration and faculty.

The elements that create a positive teaching culture are well established in the professional literature. Through the voices of actual practitioners, this paper is intended to encourage first steps toward putting some of those elements into practice.

Positive Teacher Culture: Teacher Views

Allison Hunt, a former Kentucky Teacher of the Year and Hope Street Fellow, teaches AP Human Geography at DuPont Manual High School in Louisville’s Jefferson County Public Schools (JCPS). Hunt believes that to elevate the teaching profession, teacher roles should be differentiated based on varied responsibilities, including those that call on current classroom teachers to exert leadership. She deplores what she terms the traditional “egalitarian ideal” of teaching that requires all teachers to do the same things in the same ways regardless of teacher strengths and student needs. She notes that accomplished teachers who work to distinguish themselves often meet with disapproval from administrators and peers. “The very worst thing that ever happened to me in my building was becoming Kentucky Teacher of the Year,” she says, explaining that she felt shunned by some colleagues as a result. “It’s the factory mindset. Creativity and doing something out of the box is bad when you’re on the (assembly line).”

Allison Hunt, a former Kentucky Teacher of the Year and Hope Street Fellow, teaches AP Human Geography at DuPont Manual High School in Louisville’s Jefferson County Public Schools (JCPS). Hunt believes that to elevate the teaching profession, teacher roles should be differentiated based on varied responsibilities, including those that call on current classroom teachers to exert leadership. She deplores what she terms the traditional “egalitarian ideal” of teaching that requires all teachers to do the same things in the same ways regardless of teacher strengths and student needs. She notes that accomplished teachers who work to distinguish themselves often meet with disapproval from administrators and peers. “The very worst thing that ever happened to me in my building was becoming Kentucky Teacher of the Year,” she says, explaining that she felt shunned by some colleagues as a result. “It’s the factory mindset. Creativity and doing something out of the box is bad when you’re on the (assembly line).”

“I have to beg for professional leave time for awesome opportunities that are clearly going to enhance my teaching and learning for my students. Why?”

In addition to differentiated teacher roles and responsibilities and new opportunities for teacher leadership, Hunt advocates for increased teacher voice and flexibility in determining professional learning tailored to self-identified needs. “I have to beg for professional leave time for awesome opportunities that are clearly going to enhance my teaching and learning for my students,” she says. “Why?”

Kip Hottman is in his thirteenth year teaching Spanish, currently at Fern Creek High School in JCPS – but it wasn’t until about two years ago that he came to appreciate the power of professional learning to expand and inspire his work in the classroom. A recent Hope Street Teacher Fellowship and participation on a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation teaching advisory panel made Hottman aware that teachers need to connect both within and across schools, districts and states. In the past, he says, “I thought connecting (with other teachers) was walking across the hall.” Now he asks instead, “How do you know who is fabulous at (teaching) what, and where?”

“I feed off the passion and the networking and the learning from being around other teachers.”

Hottman says mobile technology applications like the Boxer email management app, and JCPS Forward, which facilitates informal, online district-wide teacher chats, help make professional learning more flexible and expand its scope. He estimates some 200 JCPS teachers currently connect through JCPS Forward. In contrast, Hottman describes his first 10 years of teaching as “isolated.” Thanks to new opportunities to interact virtually with colleagues nationwide, he now says, “I feed off the passion and the networking and the learning from being around other teachers.”

Like Hottman, twelfth year teacher Paul Barnwell has come to believe that collaboration and new approaches to professional learning are essential to lifting the profession. Currently teaching English half time at Fern Creek High School in JCPS while also serving as a Center for Teaching Quality (CTQ) teacherpreneur who launches virtual professional learning communities, Barnwell cites the creativity and autonomy he enjoys in his dual role facilitating both classroom instruction and online professional learning for colleagues – including through a Gates Foundation-funded program called Classroom Teachers Enacting Positive Solutions (CTEPS) through which teachers virtually brainstorm approaches to school and district challenges.

Like Hottman, twelfth year teacher Paul Barnwell has come to believe that collaboration and new approaches to professional learning are essential to lifting the profession. Currently teaching English half time at Fern Creek High School in JCPS while also serving as a Center for Teaching Quality (CTQ) teacherpreneur who launches virtual professional learning communities, Barnwell cites the creativity and autonomy he enjoys in his dual role facilitating both classroom instruction and online professional learning for colleagues – including through a Gates Foundation-funded program called Classroom Teachers Enacting Positive Solutions (CTEPS) through which teachers virtually brainstorm approaches to school and district challenges.

In a recent CTQ blog post, Barnwell recalled the “overwhelmingly difficult first year,” that nearly drove him to leave teaching. He believes collaboration in person and online is essential to address teacher burnout and offset the potentially daunting experience of working with students alone in a classroom all day. Barnwell supports peer time built into the workday for teachers, including teacher-led professional learning, and differentiation of teacher roles and workloads based on the needs of students.

Barnwell says he’s fortunate to have a principal who is open to trying new approaches to promote teacher leadership and learning. “I could imagine a system with structures in place (for) alternating face-to-face and virtual professional learning sessions, with teachers and outside experts connecting across schools and content areas,” he says, noting the “almost infinite possibilities of people” with and from whom teachers can learn.

Positive Teacher Culture: Informal School Level Change

A small public high school in eastern Kentucky supports the teacher views cited above that collaboration and autonomy are critical to successful classroom practice.

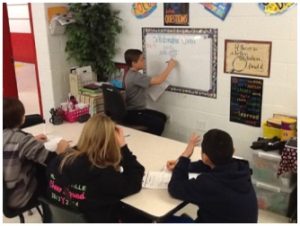

Ricky Thacker recently drew the attention of Microsoft founder Bill Gates, who visited his mathematics classroom at Betsy Layne High School in Floyd County. Gates later blogged about Thacker’s unconventional approach to instruction in a brightly painted classroom with whiteboards on every wall and a giant x-y axis taped to the floor in place of desks. Gates described Thacker, “calling out coordinates…as students rushed around him from quadrant to quadrant. Everyone was engaged, including me.”

“When I wake up every morning I’m always excited to come here. I don’t think of what I do as a job. It’s fun, it’s rewarding, it’s fulfillment.”

We interviewed Thacker to find out how he came to create his unique classroom environment. Now in his ninth year of teaching at Betsy Layne, Thacker grew up in nearby Pike County, Kentucky. His father was a coal miner, his mother worked in a local grocery store, and Thacker was the first in his immediate family to go to college. A teacher of Algebra I and mathematics intervention classes, he describes Betsy Layne as a “data-driven school” focused on using data to better meet student instructional needs. He also describes Betsy Layne as “a family,” noting, “When I wake up every morning I’m always excited to come here. I don’t think of what I do as a job. It’s fun, it’s rewarding, it’s fulfillment.”

Thacker credits Betsy Layne Principal Cassandra Akers for the school’s positive teaching culture. Akers welcomes out-of-the-box ideas based on student data, he says, encouraging teachers to offer new approaches to student learning challenges. “She allows us to express our educational philosophy in our room,” he says. “If it’s in the best interests of the students, we try every avenue possible to do that.”

Thacker was inspired to change his approach to teaching by a Kentucky Valley Educational Cooperative workshop on the value of discovery learning presented by Dr. Thomas Murray of the Alliance for Excellent Education. Thacker stopped lecturing from the front of the classroom, and started instead guiding students to work through problems together. Now, he says, “I can say something 20 million times, and a student will never get it, but if another student explains it, the light bulb goes on.”

“We’re accountable to the kids. If you take care of them, the other stuff will take care of itself.”

For her part, says Principal Akers, “I don’t take credit for anything going on in the classrooms. I do take credit for putting together a great staff. If they can tell me why (they want to do something) and tell me how, we try it. We’ve failed a lot, but we’ve been successful a lot.” She says she and her staff do talk about test scores, constantly comparing themselves to other schools and striving to improve. But, she adds, “We’re accountable to the kids. If you take care of them, the other stuff will take care of itself.”

It’s no wonder Betsy Layne feels like a family to Thacker. Akers herself is a graduate of the school, in her eighth year as principal – and her twenty-fourth working there, first as a teacher, then as an instructional coach and assistant principal. She knows the community well, and sends faculty and staff to students’ homes when necessary, helping families to “remove any barrier (to learning) we think they might have.” Betsy Layne’s 26 teachers serve 400 students in grades nine through twelve, three-quarters of whom qualify for free/reduced lunch.

Akers believes a negative teaching culture can result from trying to solve too many problems in a building at once, and often advises other principals to focus on one challenge at a time. She says the mechanics for establishing a positive teaching culture are relatively simple: With a particular focus on new teachers, Betsy Layne regularly hires substitutes so teachers can be released to observe more experienced colleagues in the classroom. Even veterans struggling with aspects of instruction or classroom management are offered opportunities to observe skilled peers. New teachers have faculty mentors within the building. Betsy Layne teachers are also encouraged and released to participate on walkthrough teams that visit other district schools and provide feedback to colleagues. Akers herself says she observes classrooms in her building at least twice a day.

Akers believes a negative teaching culture can result from trying to solve too many problems in a building at once, and often advises other principals to focus on one challenge at a time. She says the mechanics for establishing a positive teaching culture are relatively simple: With a particular focus on new teachers, Betsy Layne regularly hires substitutes so teachers can be released to observe more experienced colleagues in the classroom. Even veterans struggling with aspects of instruction or classroom management are offered opportunities to observe skilled peers. New teachers have faculty mentors within the building. Betsy Layne teachers are also encouraged and released to participate on walkthrough teams that visit other district schools and provide feedback to colleagues. Akers herself says she observes classrooms in her building at least twice a day.

In addition, Betsy Layne teachers meet in professional learning communities twice a week, with a focus on data that can help them make adjustments to meet student needs – often seeking and finding the expertise they need from within the faculty itself. “We try things without fear of reprimand,” Akers says. “We don’t approach it as a punitive thing.” Overall, she says, it doesn’t take a lot of money to provide opportunities for teacher collaboration and professional learning, “but it has a lot of benefits.”

Positive Teacher Culture: Informal District Level Change

Broadening beyond an individual school, it is also critical for district level administrators to create an atmosphere in which teacher autonomy and collaboration are encouraged and supported.

Jana Beth Francis, in her fifteenth year as Director of Assessment, Research and Curriculum in Daviess County, Kentucky, believes professional learning provides a path forward for teachers – but only if they feel as safe asking questions as they do coming up with answers. “The education system has been set up like a factory model,” she says. “Teachers expect to be told what to do. That model doesn’t work anymore. Teachers must problem solve and think.” She notes that the current crop of new teachers, who were students themselves in an era of standardization, must be encouraged to individualize their approaches. To get teachers learning again, Francis believes, it’s critical to have administrators learning alongside them. “The whole organization has to be a learning organization,” she explains. “You have to be willing to say you don’t know about something,” and to leave a professional learning session with more questions than answers.

“Teachers expect to be told what to do. That model doesn’t work anymore. Teachers must problem solve and think. Your best learning happens when you sit around and work together.”

Examples of Positive Teacher Culture: Formal School or District Level Change

Built on the same principles that guide schools like Betsy Layne High School and districts like Daviess County, there are also research-based, comprehensive models that provide roadmaps to teacher autonomy, leadership and collaboration.

Opportunity Culture is one such research-based, comprehensive model aimed at boosting student learning by transforming teacher roles throughout a school. Developed by Public Impact, an educational consulting organization based in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, the model was inspired by research indicating that top teachers – as measured by student growth – facilitate up to three times more learning for their students as other teachers.

Designed to work with existing personnel and within the existing budget of a given school, “An Opportunity Culture extends the reach of excellent teachers and their teams to more students, for more pay, within recurring budgets,” as stated on the www.opportunityculture.org website. The model provides a framework for redesigned teacher roles and increased pay based on differentiated responsibilities through reallocation of existing funds – for example, by increasing class sizes to free selected teachers to spend parts of each day working with colleagues. Unlike short term grants, reallocation of existing budgets is designed to ensure sustainability.

The professionals needed to help move any school forward are often already in place. What’s required is not necessarily an infusion of new personnel, but recognition of leadership potential, and the opportunities and support to activate it.

Central to this particular model is the designated role of Multi-Classroom Leader – a teacher with responsibility both for teaching a reduced class load and for mentoring and collaborating with a team of colleagues for additional pay. Also critical is the notion of shared accountability – that all teachers whose work touches students share responsibility for the success of those students. In addition, the model includes Expanded Impact Teachers – top teachers who, with the assistance of support staff, can meet with many more students than a traditional teacher, through virtual and face to face instruction. The model also includes Aspiring Teachers, not yet certified but salaried and mentored on the job.

Public Impact Co-Director Bryan Hassel says Opportunity Culture enables a principal to shift from single-handedly managing a large staff to working collaboratively with teacher leaders connected to students.

Districts and schools can adopt the Opportunity Culture model independently, or can opt for additional consultation from Hassel and colleagues. Regardless, Hassel believes, “Every school is sitting with a team of teachers and leaders.” That is, the professionals needed to help move any school forward are often already in place. What’s required is not necessarily an infusion of new personnel, but recognition of available leadership potential, and the opportunities and support to leverage that potential.

The Opportunity Culture model is currently being implemented in eight districts around the country, including Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina; Metro Nashville, Tennessee; and Indianapolis, Indiana. Mike York, Effectiveness Coach in the Kentucky Department of Education, has visited and communicated with several Opportunity Culture schools in an effort to learn how the model might be applied. York, who taught in Madison County, Kentucky and, for 14 years at a United States Department of Defense school in England, has a unique perspective, influenced as well by the experience of his British wife, who is also a teacher. As in the Opportunity Culture model, York says, in British schools, leadership is distributed, with principals acting mainly as building managers with responsibility for budgets, while specific teachers, who are paid accordingly, are charged with the social and emotional needs of students, departmental needs of colleagues, and so on. York believes just as teams of teachers should be held accountable for the growth of students, American schools should be held responsible for the growth of teachers.

The Opportunity Culture model is currently being implemented in eight districts around the country, including Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina; Metro Nashville, Tennessee; and Indianapolis, Indiana. Mike York, Effectiveness Coach in the Kentucky Department of Education, has visited and communicated with several Opportunity Culture schools in an effort to learn how the model might be applied. York, who taught in Madison County, Kentucky and, for 14 years at a United States Department of Defense school in England, has a unique perspective, influenced as well by the experience of his British wife, who is also a teacher. As in the Opportunity Culture model, York says, in British schools, leadership is distributed, with principals acting mainly as building managers with responsibility for budgets, while specific teachers, who are paid accordingly, are charged with the social and emotional needs of students, departmental needs of colleagues, and so on. York believes just as teams of teachers should be held accountable for the growth of students, American schools should be held responsible for the growth of teachers.

Michelle McVickers is in her fourth year as principal at one of the original Opportunity Culture schools, Buena Vista Enhanced Option Elementary in Nashville. The school population is 100 percent African American, 100 percent free/reduced lunch eligible, and 78 percent mobile – that is, lacking permanent housing. McVicker says the school draws from every homeless shelter in Nashville.

Buena Vista adopted the Opportunity Culture model as the result of a needs assessment that revealed gaps in both instructional and management expertise. Originally staffed with a 15-to-one student-teacher ratio to respond to its high-need population, the school was nevertheless falling short with a faculty largely made up of new teachers who lacked training in quality instruction. The Opportunity Culture model provided a roadmap to shift staffing from five classrooms at each grade level to three, freeing top teachers to become mentors to colleagues. The school developed an internal program to train these Multi-Classroom Leaders to respond to identified student needs. Other changes were implemented as well: In the school’s blended classrooms, instead of having a single teacher responsible for monitoring some students on computers while trying to work directly with others, teachers paired up to simultaneously implement both face-to-face and virtual learning. Top teachers were given time outside the classroom to mentor and coach new teachers, and the most capable faculty members were placed with the most needy students.

“When I got here, everybody was in their room with the doors locked. Nobody collaborated with anybody.”

“By shifting services and shifting roles, we created a development plan,” McVickers says. She says the teachers’ union was supportive, in part because teachers were driving the planning. After three years of implementation, McVickers says state assessments now show steadily increasing student proficiency in  every content area, in contrast with prior years when achievement was flat or in decline. “The biggest change,” she says, “is that when I got here, everybody was in their room with the doors locked. Nobody collaborated with anybody. There was fighting, and grievances among faculty members.” Opportunity Culture, she says, transformed the climate.

every content area, in contrast with prior years when achievement was flat or in decline. “The biggest change,” she says, “is that when I got here, everybody was in their room with the doors locked. Nobody collaborated with anybody. There was fighting, and grievances among faculty members.” Opportunity Culture, she says, transformed the climate.

McVickers advises other principals to consider what they do to support teachers and make them want to continue to be in the profession. “What grows them and develops them so they want to stay?” she asks. To improve the culture of teaching, McVickers believes, it’s critical for everyone to be honest about actual needs, to measure and plan based on what’s best for students, and to make it possible for teachers to lead planning with administrators acting mainly as facilitators. “When teachers feel valued and collaborative, and when they have a voice, they produce at a higher level,” she says. “When (teachers) own the process and have skin in the game, they believe in it. They pursue it.”

Alan Coverstone was Executive Director of Innovation in Metro Nashville Public Schools when he brought in Public Impact to help implement the Opportunity Culture model at Buena Vista. Now Assistant Professor of Education at Belmont University in Nashville, Coverstone says he was responding to the sense of isolation, fear, discouragement and disillusionment he had observed year after year, and saw the model as a budget-neutral path to empower and expand the roles of teachers. He engaged the school in a process of planning backward from long-range goals to the steps required to achieve them, and had directed his staff to help the school navigate implementation issues with the state. Ultimately, Coverstone says, he gave Buena Vista the freedom to move forward with the model, and then held them accountable for the results.

“The greatest impact a leader can have,” Coverstone says, “is to create conditions in which people can feel open and engage in honest communication and feedback about their professional practice.” Through models like Opportunity Culture, he believes, teachers feel a sense of ownership, control and self-efficacy. Coverstone advocates a teaching culture of “persistent feedback.”

In a blog post on the Opportunity Culture website, Charlotte, North Carolina teacher Romain Bertrand says the model affords teachers more influence and higher pay – and new ways of working together. Drawing on the example of another model, Coverstone notes that while Nashville Teach for America (TOA) recruits sometimes lack comprehensive knowledge of teaching strategies, TOA’s culture of ongoing collaboration and feedback nevertheless leads to measurable success with students.

“The greatest impact a leader can have is to create conditions in which people feel open and engage in honest communication and feedback about their professional practice.”

Coverstone says resistance to collaboration and feedback, and insistence on doing things as they’ve always been done – a common characteristic even and often among high performing schools – holds back teachers, and therefore students. It’s incumbent on leaders not only to transform the current teaching culture, Coverstone says, but also to ensure its future. “When that happens, we’ll attract a different group of people to the teaching profession who are engaged, engaging and more self-confident.

Key Elements of Positive Teacher Culture

Both the informal and formal or comprehensive approaches to positive teacher culture, described above, share key elements which apply across settings:

- Teacher leadership, autonomy and flexibility – applies to teacher roles, such as hybrid and “teacherpreneur,” as well as curricular and instructional practices. Teacher judgment is honored so that teachers can meet the needs of their students without strict adherence to curriculum pacing guides or overemphasis on test preparation. Schedules and class sizes can vary as can teacher pay depending on role. Moreover, administrators foster a culture of experimentation, making room for mistakes and sharing in accountability.

- Collaboration within and outside of school buildings – allows for teachers to mentor and be mentored by colleagues, to observe and learn from colleagues, to be observed by administrators and peers receiving non-judgmental, non-punitive feedback, and to connect with peers across schools, districts and states using networks and other structures. The goal of collaboration is to work together toward high levels of learning for all students.

- Enhanced professional learning – provides teachers a voice in determining their own professional learning needs, with encouragement for continued growth and support, for example in the form of released time, professional learning communities, and productive meetings that support discussion and brainstorming about school and district issues. Professional learning is directly tied to student needs from a variety of sources, including both test scores and samples of student work, teacher observations, and student interviews and surveys.

These examples reflect both normative and organizational change. For example, rethinking school norms that vest decision making only in the principal, and instead engaging teachers in identifying issues and determining solutions, can lead to greater school effectiveness for all involved—administrators, teachers and students. Changes to the organizational structure can take the form of how teachers are assigned both teaching and mentoring roles, how class sizes are determined, and how schedules can be crafted to allow greater flexibility. None of the changes suggested, whether small and incremental or larger scale, involve significant sources of funding or are dependent on the size of the school. Rural schools, as noted in the example of Betsy Layne High School, can effect significant changes in classroom practice by creating a culture that supports experimentation. Rather, these changes involve a willingness to think and act differently, and to allow the strengths and expertise of teachers to flourish, to increase their own learning and the learning of their students

Conclusion

In summary, CTL’s research and information gathering suggest that even small but significant shifts in attitude and culture within a school can have a profound and positive impact on the teaching culture. These include opportunities for teachers to take advantage of ongoing professional learning and non-punitive feedback and collaboration.

Moving away from the “factory model” that assumes that all teachers (and all students) are the same, to  achieve these changes, policy must support flexibility and autonomy at all levels. It is critical for administrators to have this flexibility as well as the capacity and inclination to learn alongside teachers, building a culture of collaboration and support.

achieve these changes, policy must support flexibility and autonomy at all levels. It is critical for administrators to have this flexibility as well as the capacity and inclination to learn alongside teachers, building a culture of collaboration and support.

Teacher roles, responsibilities, and salaries can be differentiated, based on student needs and teacher strengths. Teachers who distinguish themselves professionally can also be appropriately acknowledged and afforded opportunities for advancement in position and compensation.

When teachers are allowed to try new approaches to address student needs and teacher strengths without fear of retribution, they can strategize for the most productive paths forward, both for their students and for themselves. Shared accountability for groups of students across teams of teachers and administrators in turn eases the burden on individuals, and makes it possible for collaborators to address challenges and meet goals together.

Teacher voice and leadership must be a norm and an expectation, not an exception, and teacher support services and professional learning should likewise be designed with flexibility and customized for individuals to enable teachers to develop their strengths. In addition, these must be emphasized in pre-service teacher preparation so teacher candidates, as well as current practitioners, understand that this is expected and supported.

Above all, teamwork, face-to-face and virtual collaboration, and ongoing, non-punitive feedback distinguish positive from negative teaching cultures. Teachers should mentor and be mentored, coach and be coached, observe and be observed, and engage in professional learning throughout their careers.

To forge an enhanced teaching culture that advances both the professional standing and careers of teachers, and learning for all students, CTL urges all districts and schools to explore ways to implement these shifts in attitudes and approaches, both informal and more comprehensive.

References

Alliance for Excellent Education. What Keeps Good Teachers in the Classroom? Understanding and Reducing Teacher Turnover. February 2008.

Berry, Barnett. Children of Poverty Deserve Great Teachers: One Union’s Commitment to Changing the Status Quo. Center for Teaching Quality and the National Education Association. September 2009.

California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. Report on New Teacher Induction. September 2015.

Center on Education Policy. Listen to Us: Teacher Views and Voices. May 2016.

Commission on Effective Teachers and Teaching (CETT). Transforming Teaching: Connecting Professional Responsibility with Student Learning. Report to the NEA. November 2011.

Darling-Hammond, Linda, Ruth Chung Wei, and Alethea Andree. How High-Achieving Countries Develop Great Teachers. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education Research Brief. August 2010.

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC). “Success for Beginning Teachers. The California New Teacher Project 1988-92.” Accessed September 9, 2016. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED350262.

Martin, Carmel, Lisette Partelow, and Catherine Brown. Center for American Progress. Smart, Skilled, and Striving: Transforming and Elevating the Teaching Profession. November 2015.

Mehta, Jal, Victoria Theisen-Homer, David Braslow, and Adina Lopatin, in consultation with Robert Ettinger, Kelly Kovacic, and Doannie Tran. From Quicksand to Solid Ground: Building a Foundation to Support Quality Teaching. Harvard University Graduate School of Education. October 2015.

New Teacher Project, The. The Irreplaceables: Understanding the Real Retention Crisis in America’s Urban Schools. July 2012.

“Report: Advancement Opportunities Could Improve US Teacher Quality.” Educationnews.org. Accessed January 25, 2016. http://www.educationnews.org/k-12-schools/report-advancement-opportunities-could-improve-us-teacher-quality/. (National Center on Education and the Economy quote, page 2)

Thorpe, Ronald. “Sustaining the Teaching Profession.” New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 26: Iss. 1, Article 5.