I recently cleaned out my files and bookshelves with the goal of keeping only the essentials I want and need for providing professional development and support for educators. In the purging process, I came across Ted and Nancy Sizer’s gem from 1999 titled, The Students are Watching: Schools and the Moral Contract. I have long thought that this is a book to savor, to revisit, to keep for use when someone is ready for the conversation. Change agents know that timing is critical to getting anyone to listen to one’s message.

Perhaps there is a growing cadre of people with a ready lense to see and think about the talking points in the book. Consider this knowing statement, from page 18: “To find the core of a school, don’t look at its rulebook or even its mission statement. Look at the way the people in it spend their time—how they relate to each other, how they tangle with ideas.”

In today’s school climate, we can speculate about idea-tangling occurring in Professional Learning Communities (PLCs), teams, and faculty meetings. But we should not differentiate between our experiences and norms for adult interaction and those of our students, especially when it comes to tackling issues we face. An authentic approach to teaching problem-solving in the classroom involves using an honest approach, one that will work in the classroom as well as in a team meeting. If problem-solving is truly what students should do in school, then we might take a look at how we approach it within our own work.

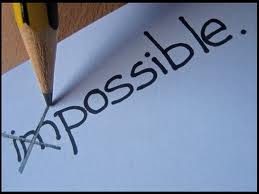

While I can think of many current structures and initiatives with which schools struggle, I am increasingly convinced that the process of collective school improvement is just as important as the content with which we grapple, and these days, they are sounding like the same thing. As standards shift us away from teaching to one correct process or answer when there are many, a professional struggle we are seeing in schools is with, well, how to struggle well.

Mistakes and failure are inevitable in parenting, in teaching, in leading. We can’t escape the simple fact that we will not know every answer, especially not immediately, and will sometimes not even know how to begin solving a problem or issue. To move forward, we admit what we do not know. We seek help from others. Sometimes that means just asking our friends and colleagues. Sometimes, it means seeking expert opinions or going online and researching what solutions exist.

Sometimes it means that some members try one solution while others try an alternative. It almost always means that it takes time, communication, and a search for evidence. Are we modeling for students that when we are stuck on an issue we have a thoughtful process for tangling with it and one that, with persistence, communication and evidence, will get us to a better practice than currently in place?

The Sizers point out that there is a curriculum from which students learn, but it won’t be found online or in teacher resource binders. It is the curriculum of process, of students’ observations about the gap between what adults say and what they do.

Are we teaching students that making mistakes, struggling, and even failure are inevitable parts of life? How are we modeling our own experience? When students get stuck on a problem, can’t understand a lesson, or have no idea how to proceed on a project, are they taught the skills of persistence, patience, and solution-seeking? Do we let them do what we do—ask friends, consult with experts, try things out, seek what works, see what doesn’t work, wallow for a while, regroup and revise?

Perhaps most importantly, are we communicating to them that they can be resourceful in solving their problems, and allowing for that resourcefulness in our classrooms? Couldn’t parents, with their life experiences, provide some support both in the classroom and out as we explore the value of struggle and failure along the path to solutions?

Alix Spiegel writes about contrasting cultural views regarding struggle in this Mind/Shift article, Struggle Means Learning, explaining that “the way you conceptualize the act of struggling with something profoundly affects your behavior.”

Such information is powerful in the hands of parents and teachers who understand their influence over how students perceive themselves as learners and whether children and adolescents think their success is related to intelligence. As this article about the work of Stanford researcher Carol Dweck explains, studies suggest that if students believe the most important factor in success is intelligence rather than effort, they are less likely to persevere through challenges.

Information connecting mindsets to such survival skills as resilience, persistence, and patience with struggle can certainly inform educators who are taking seriously the challenge of preparing all students for career and college success. Called “soft skills” in some curriculum, the concept of “can do” can be transformational in all classrooms if teachers will allow real world problem-solving to occur, and that includes room for struggle and failure along the way to progress. Add real-world collaboration possibilities to the mix, and students should experience possibility where they once saw barriers.

In her blog called Making Friends with Failure, writer Ainissa Ramirez provides a concrete example of how scientists re-frame failure they experience in their research. They call it data.

Perhaps such approaches could help educators meet the moral contract inherent in the act of teaching, as described by the Sizers: “Young people should be different—better—for their experience (at school). They should know some important things, they should know how to learn additional important things, and they should be in the habit of wanting to learn such important things.”

The students are watching us struggle. What are we modeling for them?