Background:

Background:

Taking notes from teacher presentations or from text or electronic material is an expectation for students beginning in the intermediate grades that increases at each level: middle school, high school and especially college. For some students, figuring out what to record is difficult and confusing, and they often lack organizational schemes for making sense of new information.

Taking good notes requires a number of skills including distinguishing important from less important information, organizing information to connect ideas, and making meaning from new information. There exist in the research literature a variety of strategies for giving students a structure for notetaking that will aid them in understanding and mastering content (Teaching for Results, 2003).

Definition:

Notetaking is a strategy for recording key points and important ideas from a lecture, video presentation or text material. A variety of note taking schemes exist helping students to organize and review their notes for assignments and test.

What the Literature Says About the Efficacy of Student Note Taking

The research literature on student notetaking yields mixed results on whether students are able to understand and retain information by taking notes, or are better prepared to perform well on tests after reviewing their notes (Beecher, 1988). An ongoing debate has centered on whether notetaking aids semantic encoding of information, with some studies supporting this idea (Hult et al. 1984 cited in Beecher, 1988) and others showing little or no impact on information recall (Henk and Stahl, 1985, cited in Beecher, 1988). A more recent literature review from Vanderbilt University (2014) cited Robert Williams and Alan Eggert’s 2002 literature review which focused on notetaking efficiency, “defined in terms of the ratio between the number of conceptual points recorded and the number of words in the notes” (p. 175). They concluded that the literature on student notetaking skills was mixed, especially in relation to factual recall.

However, other researchers approach the purposes and outcomes of student notetaking from a different lens. Boch and Piolat (2005) drew on the fields of cognitive psychology, linguistics and teaching science to identify notetaking as a form of writing across the curriculum, helping students to learn and to learn to write. Their research examines four aspects of notetaking: “(1) the principal functions of notetaking: ‘writing to learn’; (2) the main notetaking strategies used by students; (3) the different factors involved in the comprehension and learning of knowledge through note taking; (4) the learning contexts that allow effective notetaking: ‘learning to write.’” (2005, p. 101). They cite the importance of both the act of notetaking and the reflection that follows, noting techniques such as re-reading, highlighting and summarizing.

Rutgers’ researcher Joseph Boyle approached to topic of note taking in relation to middle school students with learning disabilities, referencing that these students in particular are poor notetakers and need scaffolding in how to take notes (2010). His experimental design study looked at 40 middle school students with learning disabilities and focused on notetaking in science classes. Half the students took notes on videotaped science lessons without any instruction on notetaking; the other half were taught “strategic notetaking” to use with the same lessons. Strategic notetaking has students identify the day’s topic, record three-six main points with details as they are being discussed, describing how ideas are related and noting new vocabulary, in an iterative process they repeat throughout the lecture, and then at the end of the lecture, recording the five most important points and related details. The results of Boyle’s study showed that strategic notetaking, when taught to and used by students, significantly increased both short and long term recall, comprehension, and the number of lecture points and words, as compared to the control group that use conventional note taking methods. While his study focused on middle grades and students with learning disabilities, the idea of teaching students to use a template for notetaking could certainly have wider application.

More recently, renewed interest in college readiness and postsecondary success has caused education researchers to take another look at notetaking as an essential skill. David Conley’s work at the EPIC Center in Oregon has promoted a four-part model for college readiness, one part of which involves student mastery of study skills including note taking (2008). In a related article published in ASCD’s Educational Leadership (2008), Conley noted that schools need a comprehensive college preparation program that includes not only cognitive skills, content knowledge and understanding of the college context, but student self-management skills that help students keep track of large amounts of information and access that information for assignments and tests. Harvard Research Fellow Michael Friedman concluded from his own research and that of colleagues: “Good note-taking practices can potentially make the difference between efficient study behaviors, better course outcomes, and even retention of course content beyond a course’s conclusion” (2014).

Strategies for Note Taking

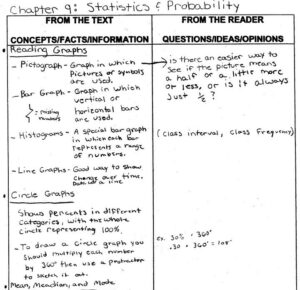

Double Entry Organizer

Purpose: The Double Entry Organizer (adapted from Teaching Reading in the Content Areas, If Not Me Then Who?. Billmeyer and Barton, 1998) is for use during and after reading/lecture/viewing. It is intended to provide scaffolding and guidance for students to take notes during consumption of information, to reflect on those notes – generating questions about the content, ideas/connections, analysis, and opinions about what they have consumed. In addition, students can use the Double Entry Organizer after consuming content to discuss their notes in small or large groups and can maintain completed organizers as reference for independent study.

Process: Provide the Double Entry Organizer (no customization of the organizer is necessary) to students.

- During initial use, take time to talk about the distinctions between facts and information from the “text”, and student response to the content.

- In addition, during the gradual release process, provide multiple completed models to students as examples of different ways they may choose to use the organizer (bullets, drawings, questions, statements, reflective notes, etc).

- As students learn to use the DEO, it is valuable to do think alouds with students modeling how you might capture the notes from a text/lecture/video to provide students understanding of how they can capture what they are learning.

- This process is best accompanied with release of the think aloud process to include student sharing of what they captured on the organizer (during the process not just after).

- As students’ progress in their use of the organizer, make blank copies regularly available for students to use at any time that they find the tool useful during and after interaction with content.

- To further create engagement with the tool design purposeful interactions with already created DEOs (i.e. in small groups review the notes from a specific tex/video/day to identify the key important details or review a specific example for key characteristics)

- Work with students to create study guides based off of their DEOs to develop their capacity to ‘study’ from their own notes rather than provide them a completed unit study guide. This process develops their capacity to identify critical material and provides you a formative assessment for content that is identified by all or most of the students as critical and content this is not.

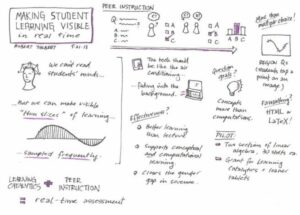

Doodle or Diagram Notes

Doodle notes take advantage of students making connections between new material and their prior knowledge. They also enable student to create personal visual pathways to creating schema around new concepts and words (Mates, & Barbu, 2016). Student control of the notes creates greater concentration as does the task of creating visual representations which has a positive impact on student learning (Holmes et al., 2010). Doodle notes are not random drawings but protocols that students use to make sense of the lecture:

- Full-color versus one color to be able to differentiate ideas

- Doodle continuously throughout the activity including words where valuable to the notetaker

- Diagram the content visually using specific icons (arrows, symbols, graphs)

- Stick as close as possible to what is said during the activity

From Robert Talbert: Real Time Assessment in Bruff (2014)

From Robert Talbert: Real Time Assessment in Bruff (2014)

Typed vs. Written Notes

Finally, some recent studies have focused on whether using technology, such as a laptop computer, can increase students’ efficiency in note taking and their recall and understanding of content. Several studies have compared performance on tests of factual recall and conceptual understanding based on one group taking lecture notes on a laptop and the other group taking notes in longhand. Some students were tested half an hour after the lecture, and some one week after the lecture and encouraged to review their notes. The researchers found that very little difference can be found between the two groups (Morehead, Dunlosky, & Rawson, 2019; Witherby, & Tauber, 2019). A study by Mueller and Oppenheimer (2014) did find slight differences on delayed questions about both factual recall and conceptual understanding for the students using longhand to take notes, even though students using a computer had taken more notes.

Additionally, as students are transitioning to more technology enhanced approaches, they are likely to take pictures of notes/diagrams/charts because it is more efficient and exact (Mueller & Daniel, 2014). The images provide detail they are likely not able to capture when writing or typing. It is still supported that students who take pictures and further engage with the diagrams and charts have greater recall and understanding.